LATEST: Prep School Open Morning

LATEST: Senior School Open Morning

LATEST: Sixth Form Open Evening

LATEST: Prep School Open Morning

LATEST: Senior School Open Morning

Back

- Nursery

- Prep

- Senior

- Sixth

- Home

- Contact Us

- Admissions

- Boarding

Since retiring as Head of Chemistry Mike Thompson (1980-2006) has shared with us the exciting news about his book The Penguin Lessons, which has been made into feature film starring Steve Coogan. Mike, who goes under a pen name as writer and artist Tom Michell, looks at how one moment of chance had a remarkable impact on the life of an author.

How one penguin’s survival led to an invasion on a beach in Barcelona

Or the serendipity that followed from the rescue of an oil-drenched bird on the Uruguayan seashore

“I really can’t believe it!” said my editor at Penguin in a frosty and injured tone. She had phoned me moments after my BBC interview that morning. ‘You’ve just ticked off John Humphrys on Radio 4’s Today programme. Live… on air!’ She had set up the broadcast some days before and I had gone through the facts carefully with three separate programme researchers. ‘Not really,’ I said. ‘I simply told him my name was ‘Michell’, not ‘Mitchell’, and that the penguin wasn’t a pet, as he called it, but was a wild bird that had refused to return to the sea and had elected to come with me after I had spent hours cleaning it of oil and tar.’

That Today programme interview was just one of the many very unexpected twists and turns that my life was to take after my spur-of-the-moment decision to rescue the little Megellanic penguin that I came across in the wake of an oil spill off the Uruguayan coast in 1976.

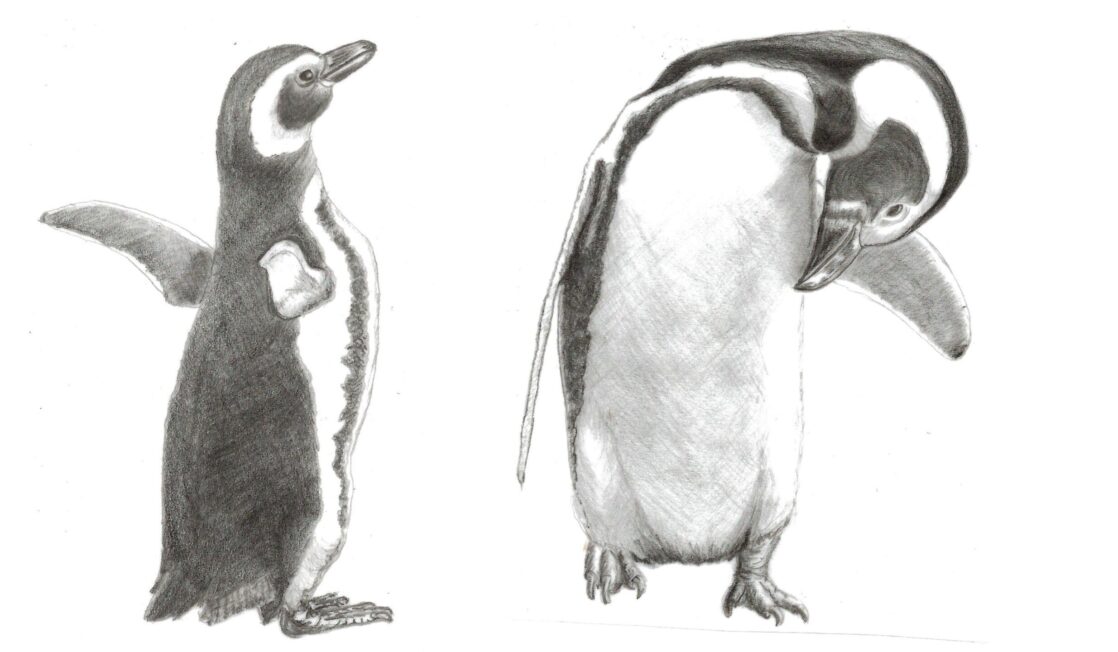

Megellanic penguins (Copyright-oceanwide-expeditions.com)

I was living in Argentina at the time, where I was teaching at a prestigious Buenos Aires boarding school, and was taking a holiday in the fashionable resort of Punta del Este on the Uruguayan coast, staying in an absent friend’s rather smart flat. The day before I was due to return to Buenos Aires and work, I had gone out for a final walk along the shore to the north of the point. It was here, on the beach, that I stumbled upon the first of what proved to be thousands of dead, oil-drenched penguins. This wasn’t so many years after one of the world’s worst environmental disasters which had seen the SS Torrey Canyon run aground off the Cornish coast, spilling some hundred million litres of crude oil. During the clean-up that followed, I had seen how it was possible to rescue and clean seabirds that weren’t too badly affected.

As I made my way along that beach, thinking how grossly irresponsible, negligent and stupid humankind can be (an opinion that hasn’t changed much in the intervening 50 years), I was astonished to discover that one penguin was still alive. Just one of thousands on the beach hadn’t succumbed to the oil, it seemed. My first thought was that I ought to end its suffering. However, when it promptly struggled to its feet and made it clear that it had no intention of tolerating any such violence, I thought again. Why not try and clean it?

And that’s what I did, over the next few exhausting, painful and frustrating hours. I then tried, repeatedly, to return it to the sea. But it kept coming back and really left me no other option but to try to take it back to Argentina with me, a journey that, as I feared, would be fraught with difficulty, danger and embarrassment.

Copyright Tom Michell

Suffice to say, I eventually made it back to my flat in the Buenos Aires school, along with the bird, now named Juan Salvador, and there, on the terrace outside my flat, he settled down on an indulgent regime of sprats and love, provided by everyone who knew him, and where he lived happily ever after.

If I close my eyes I can still see Juan Salvador leaning against my feet and feel his warmth, while we relaxed on the terrace with our habitual sundowners, sprats for him and G&T for me. It had been a particularly extraordinary day (all days living with a penguin are extraordinary). ‘I ought to write a book about you,’ I told him, and he, in his avian way, regarded me, first with one eye and then the other, as if to say, ‘What would you call it? What about ‘Juan enchanted evening?’ I said.

I told the story of Juan Salvador to Christine (TS Teacher of Maths 1982-2006) on our first date and I’m not convinced that it didn’t help persuade her to marry me. Over the succeeding years, as we began to contemplate what we would do with ourselves during our approaching retirement, she constantly told me to write the story down. Eventually, I did. When my initial attempts to find a publisher proved unsuccessful, I used a local printer to produce sufficient copies as gifts for family and friends. Then, on a whim, I self-published it on Kindle, while doubting that anybody would ever find it because all ‘Penguin’ entries in the search engine returned 20 pages of ‘A Penguin guide to Compact Discs’ and other such riveting reads.

I was, therefore, astonished when in less than a week, I received a phone call from Warner Bros channel Animal Planet, asking if we could talk about the story. They wanted evidence, which immediately sent me to a neglected packing case in the garage marked ‘Argentina – to sort’, which I still hadn’t, nearly 40 years later. There, among a collection of wonderful memorabilia I was astonished to find 31 reels of 8mm cine films that I had never actually watched. Promptly I had them transferred onto DVD and I discovered 2 minutes and 17 seconds of Juan Salvado, as his name had become to his friends.

It wasn’t enough for Animal Planet. But I had no time to dwell on this disappointment as the news was followed almost immediately by a phone call from Penguin Random House, who had been alerted to the story by the publishing grapevine.

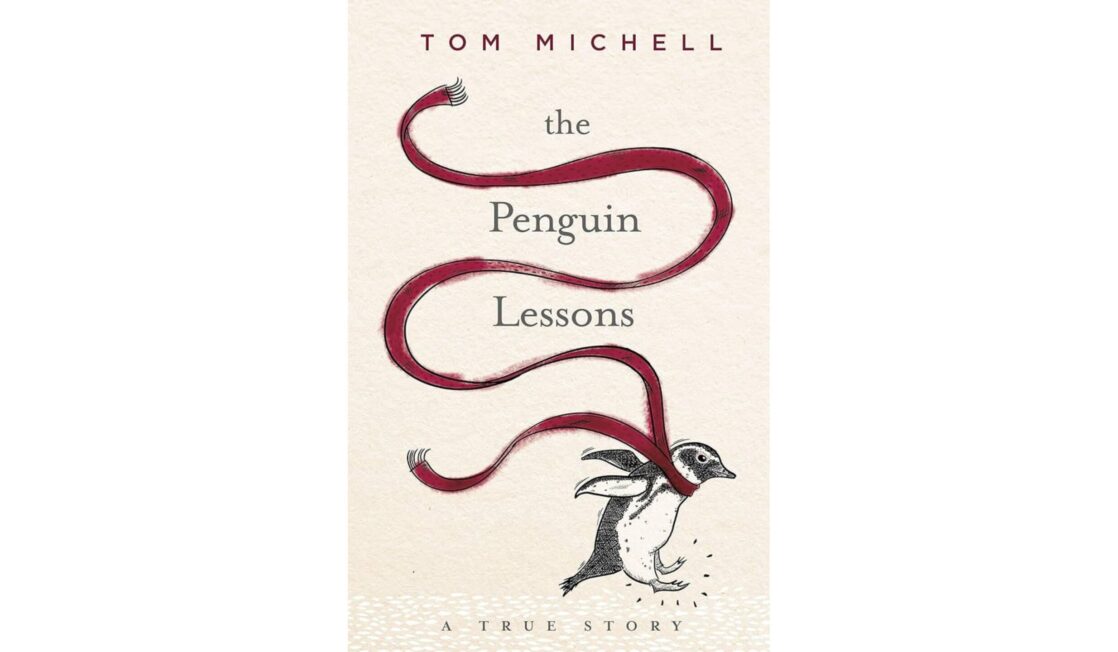

Events moved quickly after that. The hardback edition of The Penguin Lessons was published in 2015 and the paperback in the following year. Hardly a week then seemed to go by without an email advising me of another territory that wanted permission to publish it. Today the story can be read in 24 languages. The Russian edition even has delightful little flick cartoons at the corner of each right-hand page, showing a penguin diving and swimming away. Incidentally, my original draft had included a series of my own sketches of Juan Salvador, [two of which are reproduced on this page], but sadly these failed to make it to publication.

Hardly had I drawn breath, when Penguin told me they had received offers for the film rights and I better get up to headquarters and discuss any input I might have. Paperwork in place, I was introduced to Jeff Pope, head of Factual Drama at ITV who started work on the script in 2018 as I escorted him over familiar (to me) ground in Argentina and Uruguay. Everything was seemingly in place for shooting in 2019/2020. Then Covid struck, and everything stopped.

Well… not quite.

Via Penguin, I received a letter from the South Korean National Curriculum Committee asking if they might use part of the book for their English Language teaching material. Learning that a country of some 50 million (and with one of the highest educational standards in the world) should choose my work about a penguin out of all the books published in the English language, to put before their 14–16-year-olds, was a deeply humbling moment for me. Naturally, I agreed. To be completely honest, I don’t think winning one of the glittering literary prizes could actually give me a greater sense of personal achievement or satisfaction.

Next, I learned that the Cambridge International GCSE board were using extracts from the book in a couple of their exam papers. An exam taken by some 200,000 kids worldwide.

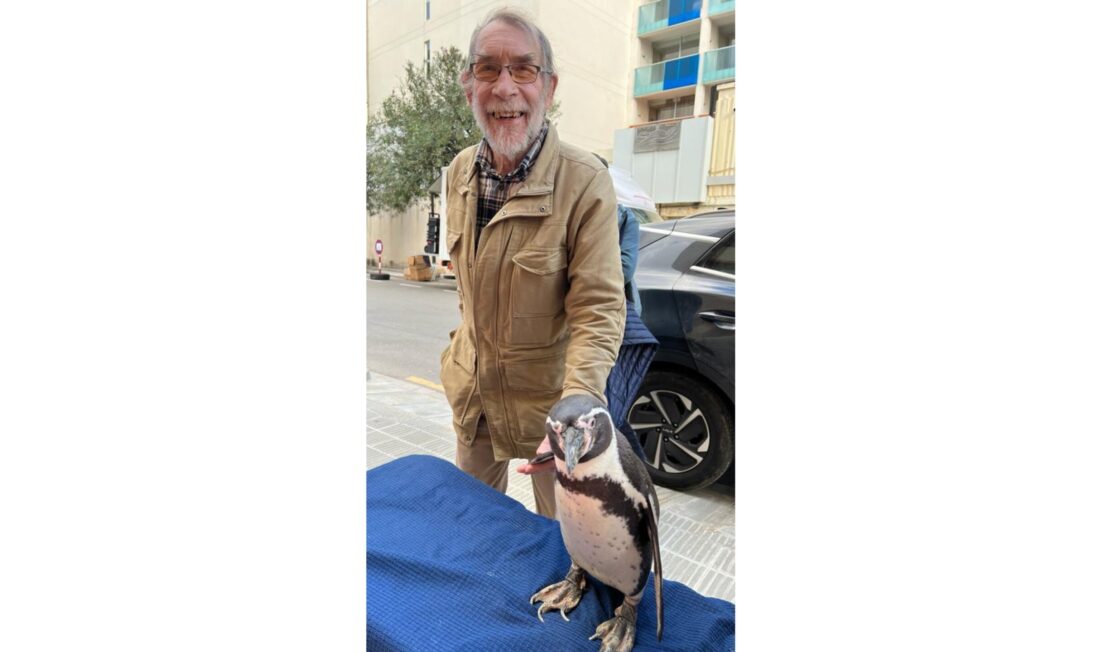

Copyright Tom Michell

What more could happen? Enter actor Steve Coogan. Jeff Pope had written screenplays for a number of films starring Coogan, and as the pandemic began to recede, during some of their collaborations, Steve asked if the penguin story could be adapted for him to play me.

So it was that, last November, I found myself on a beach, about an hour south of Barcelona, with Steve Coogan, Peter Cattaneo (director of The Full Monty) and hundreds of others, nine live Humboldt penguins, and a handful of superb animatronic models, along with a couple dozen large barrels labelled ‘Environment Friendly Artificial Pollution’ and certified by the local authority for use on the beach. As long as you look out to sea, Barcelona looks exactly like South America!

It was my first ever experience of a film set. While no single aspect particularly surprised me, I was impressed to see how the whole thing came together. The crew had taken over a corner of a village and had hired a number of buildings, including a house with a swimming pool for the penguins. There were scores of lorries with tonnes of equipment, wiring, lighting, wardrobes, make-up, camera equipment and monitors, pop-up tents, you name it. Caravans were used as green rooms and dressing rooms. An entire canteen had been set up to provide food and drink for a couple of hundred people every day – and the food was good! Nothing was left to chance. Every day, reams of instructions left nobody in doubt about what was required of them.

I had an enjoyable chat with the man who kept the penguins. He lived in France and, while there isn’t space here to record a fraction of what he told me, I was particularly impressed to learn so many different penguins were being used, each chosen for its own characteristics and its individual response to different situations. For me, it was delightful to be with real penguins again.

While there were no great revelations on the set, I was constantly enthralled. An almost military hierarchy exists within the team, from the director through deputy directors to directors of cinematography all the way down to the deputy beach-sand sweeper. The monstrously heavy gyro-stabilised video cameras were operated by chaps with the build of rugby prop forwards wearing special waistcoats with grab-handles by means of which other chaps guided, steered and stabilised the cameramen. I was impressed by the air of calm efficiency and organisation (something Peter Cattaneo attributed to the penguins). I had half expected the histrionics of a Gordon Ramsay kitchen!

From the beginning of the discussions about a film, I had been fascinated to see how all the illusions would be created. Real penguins, CGI or models? In the end, real penguins and many model penguins turned out to be the answer, along with a little CGI. Models were used for birds covered in tar, some were ‘dead’ others had to be ‘alive’, nodding their heads and flapping their wings. I spoke at length with the Spaniard whose company made the models. I can only say I was so impressed with all the facsimiles. Life size radio-controlled robot penguins with heads that look left and right, up and down, acrylic beaks that open and close, wings that flap and silicone feet. From a couple of metres away I’d defy anyone to know they were models.

To think, all this from one impulsive moment at the age of 23.

Written by Tom Michell.

Tom Michell has been writing non-fiction for more than 30 years. All his early work was commissioned by academic publishers who hold the copyrights. The Penguin Lessons is his first book of general interest and he is currently working on a new biography. Tom draws plants, birds and animals.